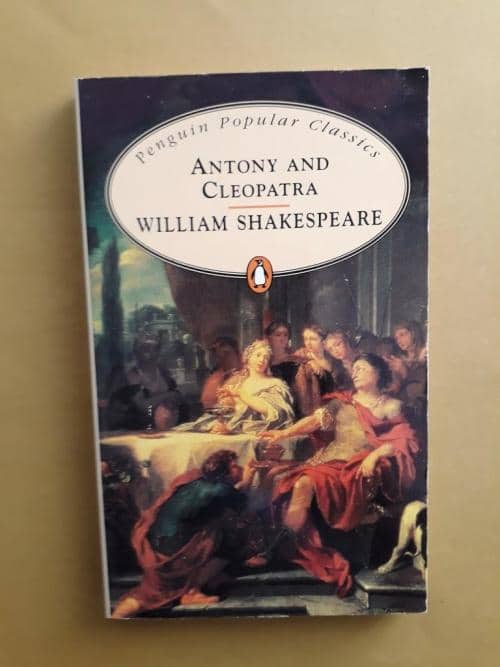

Antony and Cleopatra (English, Paperback, William Shakespeare)

Rs.299.00 Rs.99.00

Author: William Shakespeare, ISBN: 9780140620818, Condition: Old

Out of stock

This play is so good, it is not merely a masterpiece: it is a mystery. The two protagonists are alternately noble and petty, wise and foolish, and yet they never seem inconsistent or self-contradictory because Shakespeare–here is the mystery–consistently maintains a tone that is paradoxically both ironic and heroic. Part of it is the language, which shifts seamlessly from mellifluous monologues adorned with cosmic imagery (comparing Anthony and Cleopatra to continents, stars,etc.) to the most modern-sounding, most casual and wittiest dialogue of Shakespeare’s career. Part of it is the larger-than-life characterization which transforms each vicious and pathetic absurdity into a privilege of the lovers’ protean magnificence–as undeniable and unquestionable as the sovreign acts of Olympian gods. Whatever the reason, this play makes me laugh and cry and leaves me with a deep spiritual reverence for the possibilities of the human heart.

I wrote the paragraph above two and a half years ago, and it still reflects my opinion of the play. This time through, though, I was particularly struck by how much the voices of the military subordinates and servants–Enobarbus and Charmion, Ventidius and Alexis, and many others, including even unnamed messengers and soldiers–contribute to this double movement of the ironic and heroic, celebrating the leaders’ mythic qualities but also commenting on their great flaws. Enobarbus–with his loyal (albeit amused) appreciation, his disillusioned betrayal, and his subsequent death from what can best be described as a broken heart–is central to this aspect of the play.

L48

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Related products

Almost New Books

Almost New Books

Drama and Historic

Drama and Historic

Classics Book Store

Almost New Books